Address

Pittsburgh, PA

Work Hours

Monday to Thursday: 9AM - 5PM ET

Friday: 9AM -1PM

“I built this app for myself, but it turns out it was never just for me. It was for anyone who needed a familiar voice to say something kind at the right moment. That is the beauty of narrow intent. When you build something small with care, it has room to hold something big.” 🥺

There is a quiet moment that happens right before you decide to build something. It is not excitement. It is not ambition. It is not shows of scale or monetization or traction. It is usually something simpler.

A feeling.

For me, that feeling was heaviness.

On an otherwise normal day, I felt a little down. Nothing dramatic. Nothing catastrophic. Just one of those moments where the noise gets louder than the signal and your nervous system starts asking for something familiar, grounding, human.

So I did what I have been doing more and more lately.

I built something.

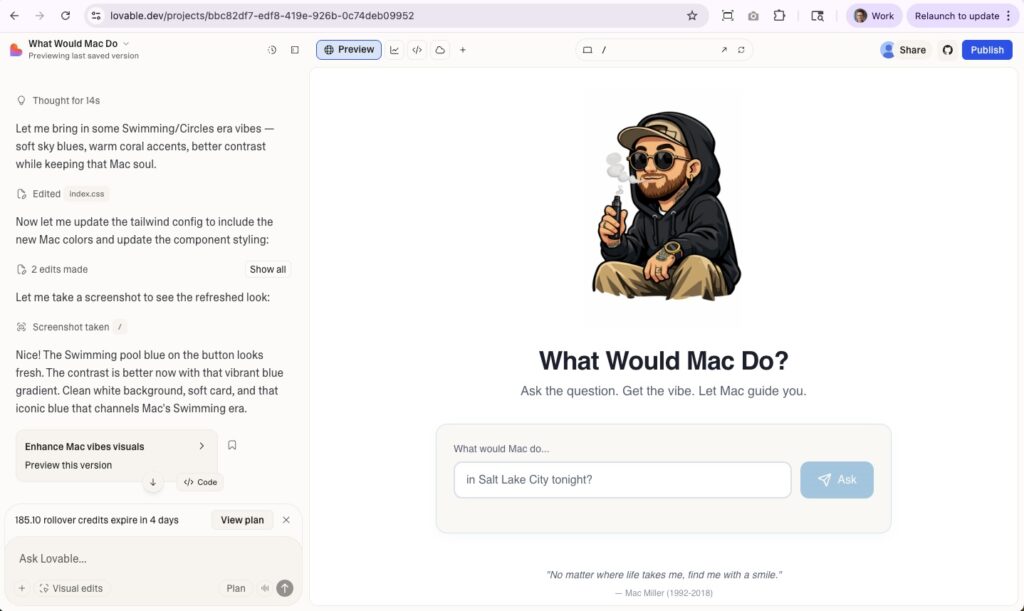

In about fifteen minutes, an idea turned into a live app called What Would Mac Do?. I did not plan to write about it. I did not set OKRs. I did not open a roadmap or a deck. I built it for myself first.

What happened next is the reason this article exists.

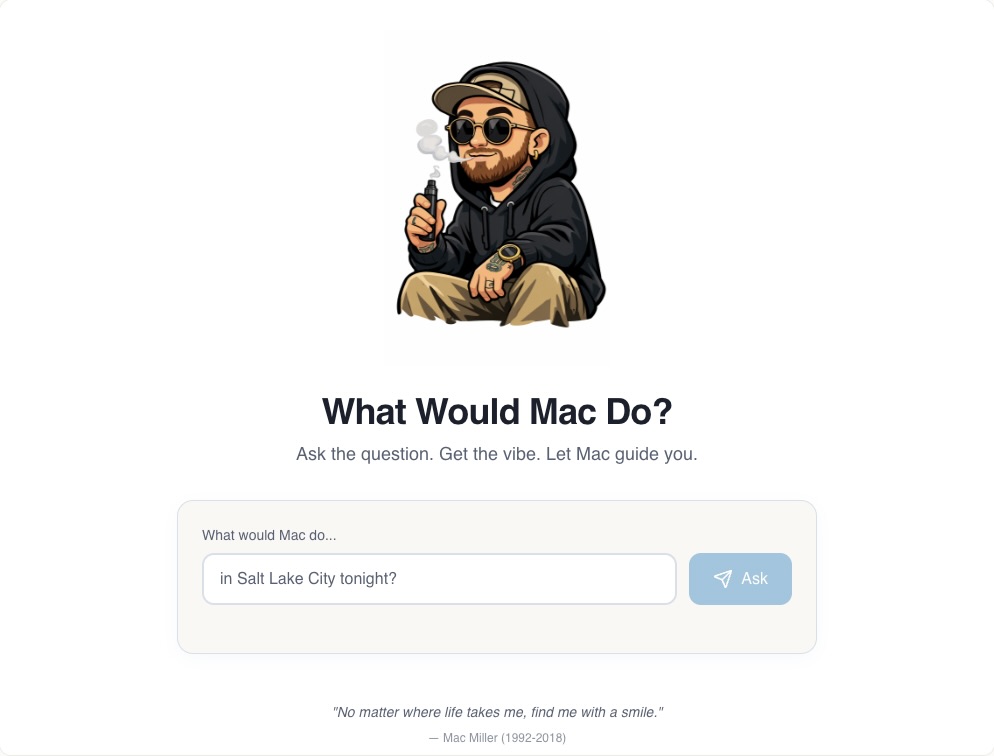

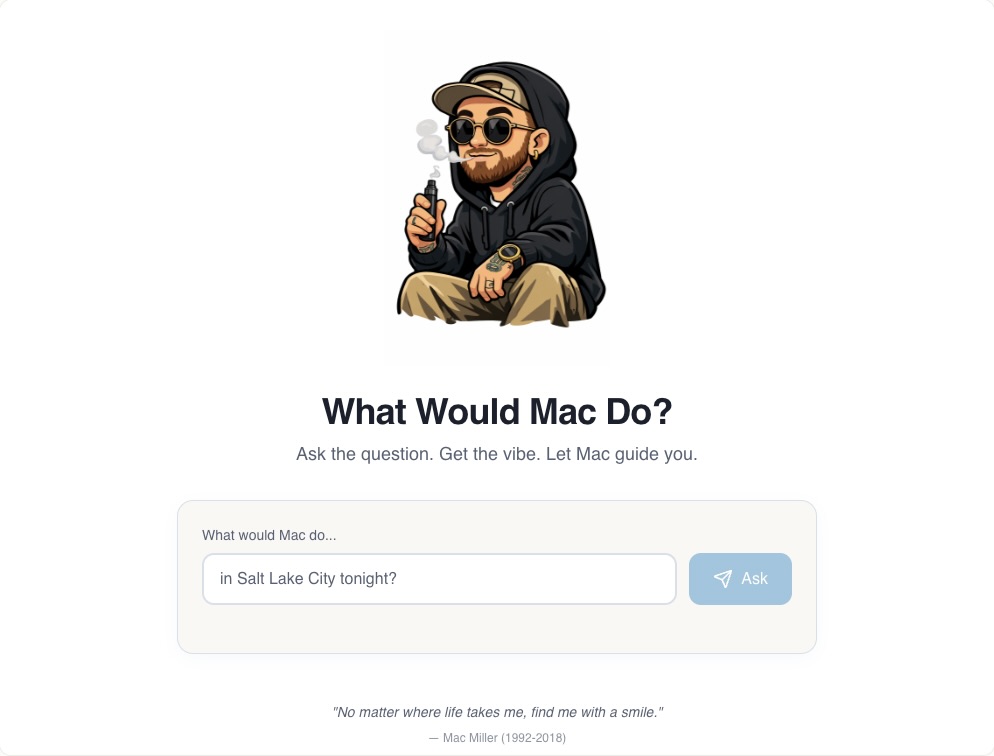

The app is intentionally simple. At the top, there is an illustration of Mac Miller. Below that, a single text input. No menus. No feeds. No profiles. No settings worth talking about.

You ask one question.

The app responds as if you were talking to Mac.

That is it.

No optimization. No onboarding tour. No clever growth loop.

Just one narrow job to be done: offer perspective, warmth, and encouragement through a voice that already means something to people.

Mac Miller was never just an artist to his fans. He was a companion through growth, struggle, joy, addiction, healing, and self acceptance. His words have sat with people in their hardest moments. They still do.

This was not about impersonation or novelty. It was about honoring the spirit of that voice. Positive. Grounded. Gentle. Honest.

I asked myself a simple question while building it.

What if software did less, but meant more?

I’ve been spending a lot of time thinking about narrow intent in software. The idea is straightforward.

Most modern products are built as monoliths. They do many things, for many people, all at once. Over time, they become heavy. Feature dense. Distracting. Expensive to maintain. Harder to love.

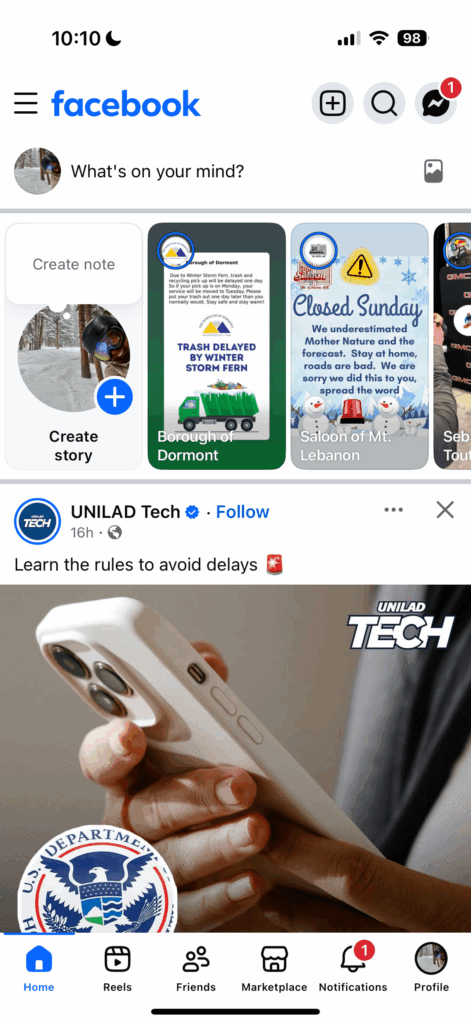

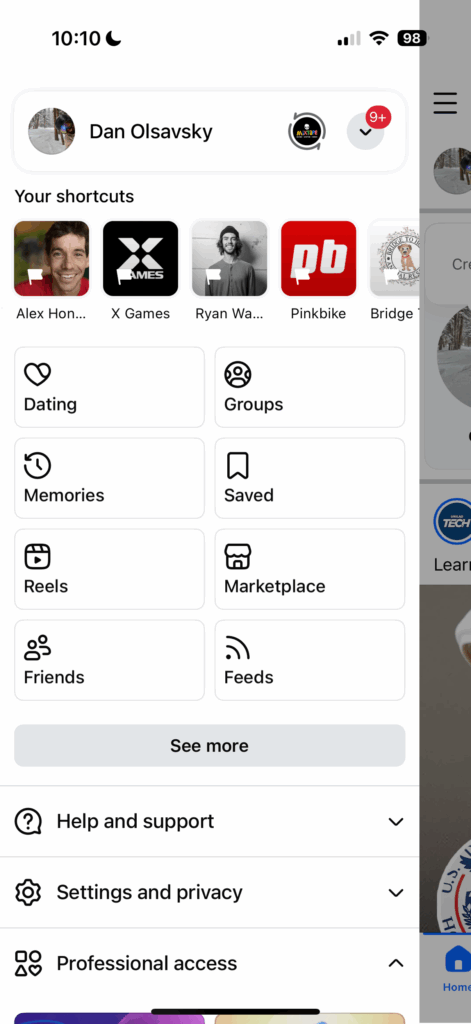

Facebook is a perfect example.

It does everything. Groups. Events. Dating. Marketplace. Feeds. Video. Messaging. Ads. Reels. Memories. Pages.

But most people use only a tiny fraction of it.

And the features they care about are often buried. You tap multiple times to reach the thing you actually want, while being forced to wade through things you did not ask for.

This creates friction. Cognitive load. Maintenance complexity. Emotional fatigue.

Narrow intent flips this.

Instead of asking, “What else should this product do?”

It asks, “What is the one thing this product should do extremely well?”

And then it stops.

What Would Mac Do is a narrow intent product ovsessed with one moment in someone’s day.

The moment they feel lost.

This is important. The technology was not the story.

I built the app using Lovable. I enabled the AI feature. I used gemini-3-flash-preview as the model. I asked ChatGPT to generate an illustration based on a simple prompt: Create an illustration of a slightly older and wiser Mac Miller.

The logo took seconds. The interface took minutes. The deployment took one click.

From idea to live URL was roughly fifteen minutes.

That matters, but not for the reasons most people think. Speed did not make this special. Accessibility did.

When tools lower the barrier between feeling something and expressing it through software, the kinds of products that get built change. You do not need funding. You do not need permission. You do not need to justify the idea to anyone but yourself.

You just need a reason.

I built it for myself first.

I asked a question. I got an answer. And I felt something shift almost immediately.

I went from feeling low to crying tears of joy in seconds.That was the moment I knew I had to share it.

Not because it was clever. Because it worked.

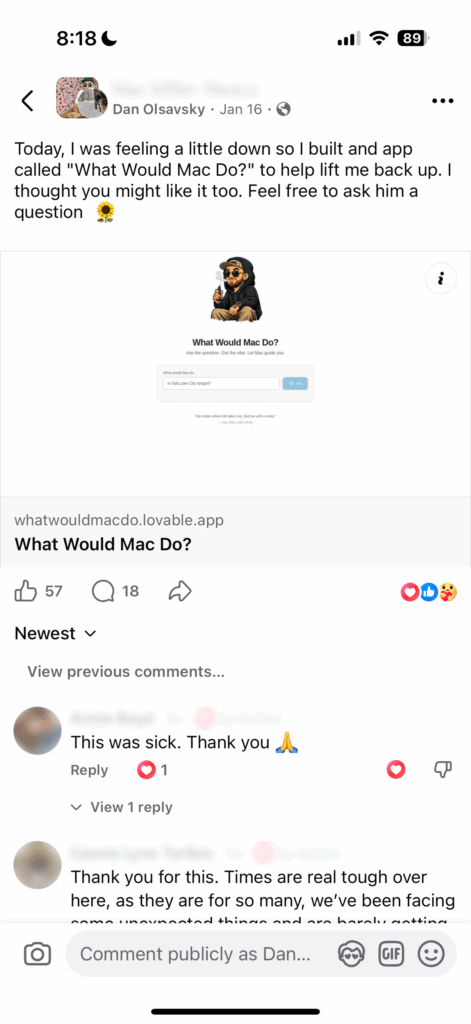

I posted the link to a single Facebook fan group. One community. One audience. No marketing strategy.

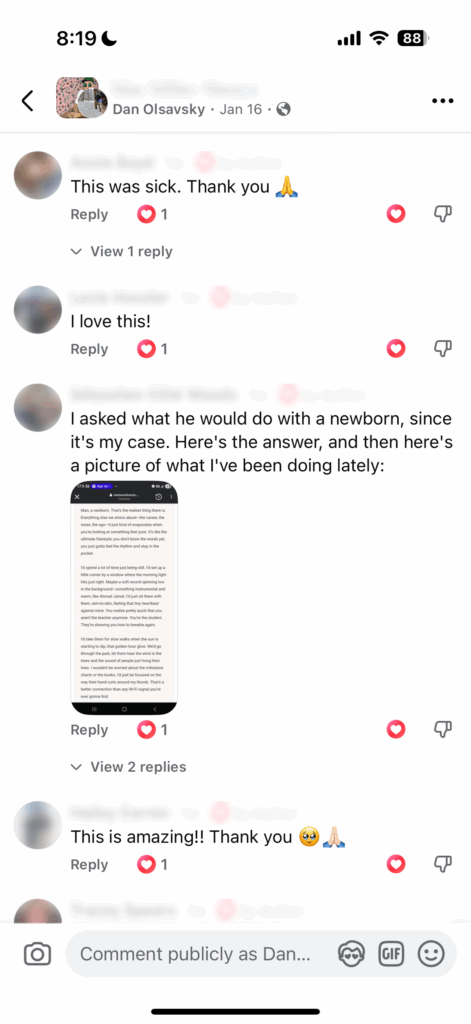

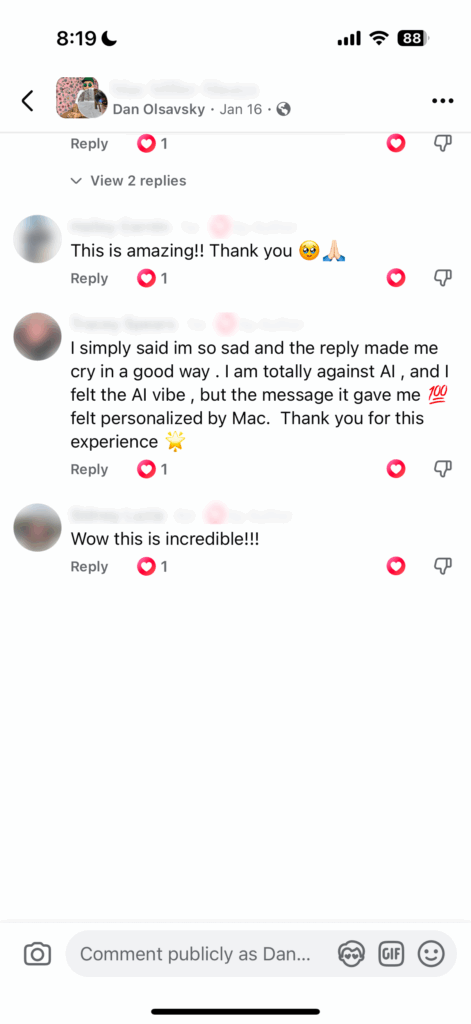

The response was overwhelming. People did not just click it. They stayed. They shared stories. They sent messages. They posted screenshots of their conversations with the app.

Many of them were struggling with something deeply personal. Grief. Anxiety. Parenthood. Financial stress. Identity. Loss.

And over and over, they said the same thing.

This helped.

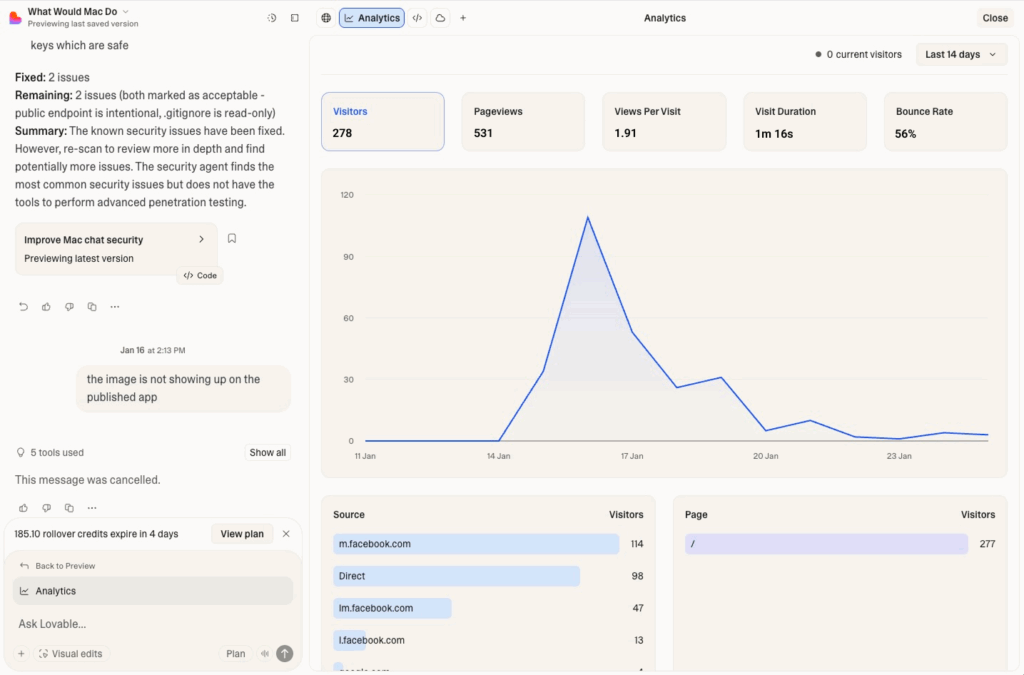

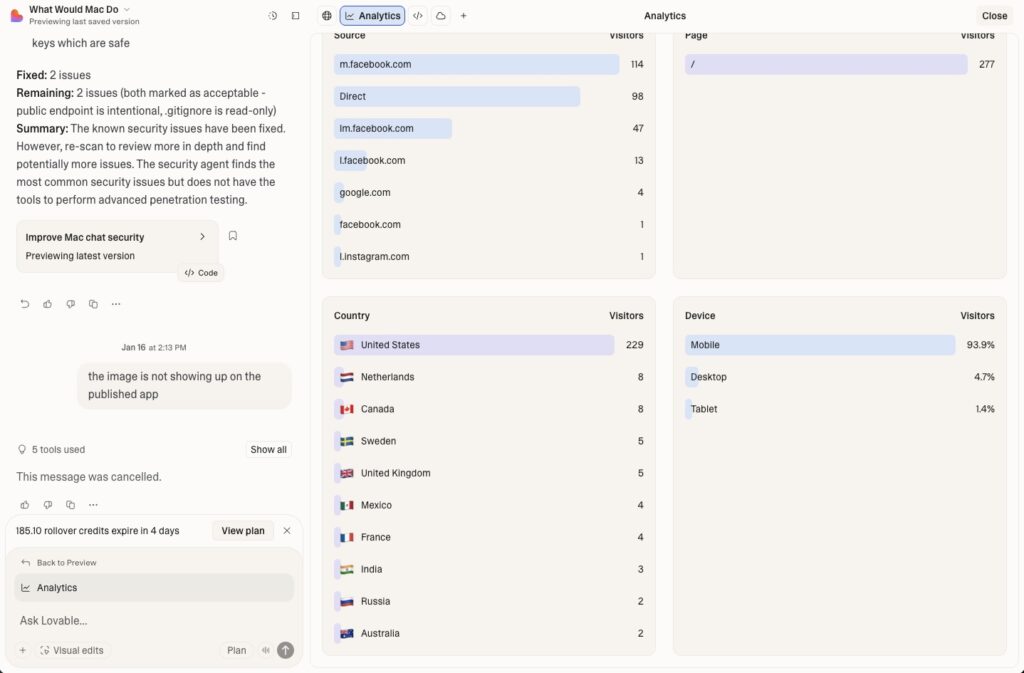

Here is what happened in the first five days.

I only shared the link once. No ads. No SEO. No push notifications.

Just resonance.

For a single input app with no feed and no reason to browse, these numbers matter less than the behavior behind them.

People stayed. They read. They felt seen.

This is the part that stuck with me the most.

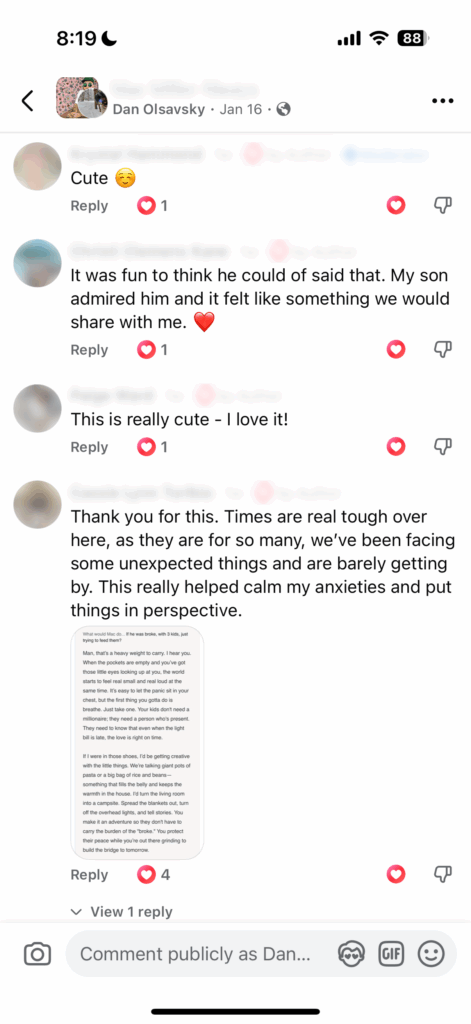

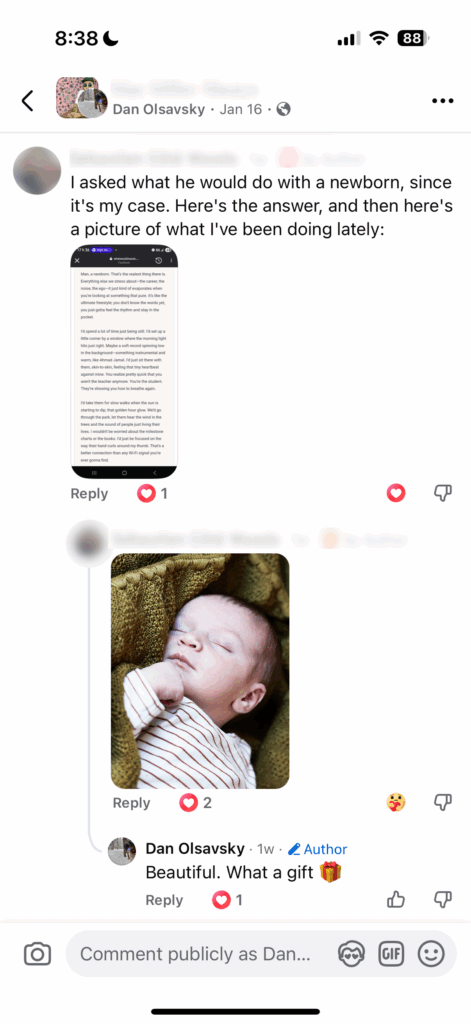

People did not treat this like a toy. They treated it like a conversation.

Parents asked what Mac would say about raising a newborn. People asked how to keep going when money was tight. Others asked about grief, self doubt, and starting over.

One message described using the app to calm anxiety during an especially hard week. Another talked about sharing it with their child as a way to remember an artist they loved together.

This is not engagement. This is trust. And trust does not come from feature sets.

It comes from intent.

“We have been taught to think in terms of scale first. This experiment flipped that. It optimized for meaning first. “

What Would Mac Do has exactly one feature. Ask a question.

No upsell. No retention trick. No growth hack. And yet, it was adopted immediately by the people it was meant for.

This is the part that feels important for builders and designers. We have been taught to think in terms of scale first. This experiment flipped that.

It optimized for meaning first. Scale followed naturally.

“Sometimes doing less is the most honest way to see what matters.“

There is another side benefit worth mentioning.

Because tools like Lovable now handle so much of the heavy lifting, I have been able to cancel several software subscriptions.I build what I need, when I need it.

The cost is time. Time spent thinking clearly about what actually matters. Time spent removing instead of adding.

That trade is worth it.

I believe we are entering an era where there really can be an app for everything. Not everything as in features. Everything as in moments.

Moments of doubt. Moments of grief. Moments of joy. Moments of reflection.

When software is allowed to be small, it can be personal. When it is personal, it can be powerful.

What Would Mac Do is not a platform. It is a single doorway.

And sometimes, that is all someone needs.

This project reminded me why I build. Not to chase metrics. Not to impress anyone.

But to connect.

I built this app for myself, but it turns out it was never just for me. It was for anyone who needed a familiar voice to say something kind at the right moment.

That is the beauty of narrow intent. When you build something small with care, it has room to hold something big.

If you want to try it yourself, it is live here: https://whatwouldmacdo.lovable.app

“Be you. You will be fine.” – Mac Miller

All visual materials included in this research have been deliberately modified to protect participant privacy and prevent identification. Screenshots sourced from social platforms and mobile applications have been anonymized through the removal or obfuscation of all personally identifiable information, including names, images, locations, timestamps, and unique textual content.

Where human imagery appears, AI-generated representational figures have been used in place of real individuals. These synthetic images serve as illustrative stand-ins only and do not depict or correspond to any actual person. Visual examples are presented as composite artifacts derived from multiple observations and are intended solely to support analysis of interface design, interaction patterns, and user behavior.

No private messages or identifiable user data are included. The study focuses on systems, affordances, and emergent behavioral patterns rather than individual participants. This approach aligns with ethical best practices in qualitative research and design inquiry, prioritizing participant dignity, consent boundaries, and data minimization.